Scars can be literal or metaphorical, physical or psychical. The scar is the memory of the wound, imprinted on the warp and weft of the flesh or in the incrassate tissue of the brain. Every scar is unique, the trace left by an unrepeatable concatenation of circumstances and events that culminate in a trauma affecting the body or mind

But the one scar that is common to all is the umbilical cicatrix. It is the primordial scar; it is the mark that unites all men (and, indeed, all living things not born from the seed or egg). For, no man can enter the world without the cord that bound him to the womb being severed and leaving its trace. The umbilicus thus also marks us as separate distinct individuals. For the scholastics, it was a subject of fierce debate whether Adam and Eve, the only humans not to have been formed in the womb, possessed a naval, the umbilical scar. Were their bellies smooth, unblemished, or when God moulded them from the red earth and the rib respectively did He fashion them an umbilicus in order not to be incomplete? Likewise, when God removed the rib from Adam's breast from which to shape Eve, did it leave a scar?

What is certain is that the scar is to be found only in the fallen world, a place of toil, disease, violence, natural shocks and heartaches. We enter the world in a state of original sin, and this entrance is thenceforth and forever marked by a scar. The umbilicus, as the first scar, is the nexus whence all other physical scars radiate, the primal node of a web of accidents, mishaps, injuries and illnesses that forms an intricate and unique map of our passage through the world. Each body has its own uniquely patterned web of scars, and each scar tells its own story. The cicatrix is thus the imprint and bearer of memory, a sign by which man is revealed in his uniqueness, in the particularity of his own unrepeatable acts and sufferings, and the marks made on him by the latter.

When Odysseus returns to Ithaca disguised as a wandering beggar, his old nurse, Eurycleia, recognises him by the scar on his leg, when, bidden by the unwitting Penelope, she washes his feet in the basin of ringing bronze. The cicatrix, once revealed, aches for its tale to be told. And at this moment of agonising suspense in the flow of Homer's epic, when it seems that Odysseus might be unmasked before he can exact his revenge on the upstart suitors, the narrative breaks off and the listener is taken back to Parnassus, whither the young Odysseus had journeyed to visit Autolycus, his mother's father, beloved of cunning Hermes. And thus begins the story of one of the most famous scars in all of literature. Hunting with the sons of Autolycus, among the windy hollows of Mount Parnassus, Odysseus corners a boar, within a glade on the steep forest-clad slopes. Charging from its deep, bosky lair, where neither the rainy winds blow nor the bright rays of Helios ever strike, the boar gashes Odysseus' thigh with its tusk, and in his turn the resourceful son of Laertes transfixes the beast with his spear. In the halls of Autolycus, on the hunters' return, the wound demands that its tale be told, the same as the scar (oulê) will demand that its memory be unfolded by the rhapsode once it is secretly revealed in the halls of Odysseus many years later, after the war on the windy plain of Troy and the many years of bitter wandering that followed. Unlike in the Odyssey, it is significant that in the Iliad, the epic of the wrath of Achilles, a narrative of never-ending fresh wounds, the word oulê (scarred-over wound, cicatrix) does not occur once.

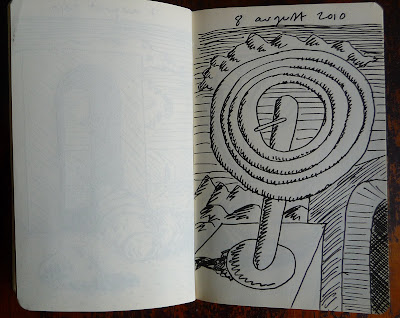

Thus, the recounting of the wound is like a scar that forms a break in the tissue of the narrative. A text itself might be full of scars, if the author, like an over-zealous surgeon, wields the critic's knife, hacking away at even the flesh of healthy passages. Cicatricosus (full of scars) is the adjective used by Roman rhetorician Quntillian in his Institutio Oratoria to describe the bloodless works of those orators who cannot resist tinkering with their manuscripts whenever they have them in their hands, in the belief that every first draft must necessarily be riddled with faults. (1) Of course, for the Romans, who for everyday purposes wrote by incising letters with a stylus upon waxed tablets, a text could be a reticulation of scars in quite a literal sense.

The mind, too, has been likened to a waxed tablet, upon which impressions are imprinted. Impressions and thoughts are incised in the mind, each leaving a deeper or shallower scar. In the Satyricon, it is said that the man of true culture must smooth all irritation (scabitudo, from scabies, "roughness") from his mind without leaving any scar. (2) Ataraxy would therefore be a state of supreme scarlessness. But just as none can enter life unscarred, life itself cannot be lived without incurring or inflicting scars. And the cicatrix is both memory and the inscription of a tale.

(1) Quintillian, Instituio Oratoria 10 4.3. Sunt enim qui ad omnia scripta tanquam vitiosa redeant et, quasi nihil fas sit rectum ess quod primum est, melius existiment quidquid est aliud, idque faciant, quotiens librum in manus resumpserunt, similes medicis etiam integra sectantibus. accidit itaque ut cicatricosa sint et exasanguis et cura pejora.

(2) Petronius, Satyricon 99. Tantum omnem scabitudinem animo tanquam bonarum artium magister delevet sine cicatrice.